Countries

This transparent monitoring project carried out case studies in four countries—Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Papua New Guinea, and Peru—to address specific needs identified by the countries, ranging from technical work related to emission factors to improving community monitoring.

Continue scrolling to read each country’s land-use emissions profile and a summary of how the project applied transparent monitoring approaches in each. For more details about the case studies, see the summary page for Book II: Case studies.

Côte d’Ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire is the largest producer of cocoa in the world, but it has long lacked a trusted data source for assessing the extent of cocoa plantations in the country and the related land-use change. The governance situation is also complex; forest monitoring competences and capacities are scattered across several institutions, including the REDD+ Secretariat (SEP-REDD) under the Ministry for the Environment and the Ministry of Forestry. The Cocoa & Forest Initiative (CFI) also has monitoring commitments but the integration into the governmental monitoring structure is unclear. Several actors, both from the private sector and the public realm are participating and competing for resources.

At the same time, The European Union (EU) is intensifying its monitoring-related activities in Côte d’Ivoire in preparation for the implementation of the EU deforestation-free law. In 2020, the EU initiated the ‘Cocoa Talks’ with Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana to devise a novel approach to cocoa sustainability. The EU has allocated substantial financial resources towards cocoa sustainability, with a portion earmarked for monitoring.

Maps were made accessible in a dedicated interactive Transparent Monitoring platform, where users can compare them and identify agreements and contradictions. Where possible, the maps are provided with metadata describing their development and limitations.

Ethiopia

The Ethiopian government places a strong emphasis on restoring degraded lands and increasing forest cover. It has established a national forest inventory, and its national system for GHG accounting and reporting (MRV System or MRVS) was built with primary technical assistance from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). There are, however, ongoing efforts to close data gaps and improve the quality and sharing of land-use and biomass data. These efforts and others are necessary to prepare Ethiopia for upcoming technical assessments related to the Paris Agreement Enhance Transparency Framework (ETF). In addition, at the time of the case studies, the country had invested relatively little into understanding and enhancing the policy and participatory aspects of their MRV system.

Since 2021, the mandate of Ethiopia’s Environment, Forest and Climate Change Commission (EFCCC), which encompasses the REDD+ secretariat, is shared between three ministerial entities:

- Environmental protection, which now reports to the National Meteorology Authority;

- Forestry, renamed Ethiopian Forest Development (EFD), which reports to the Ministry of Agriculture; and

- Climate change, which now reports to the National Planning Commission. Through this restructuring, the National REDD+ Secretariat has become part of the EFD and is therefore now under the Ministry of Agriculture, a structure in effect since October 2024.

Ethiopia carried out land cover and land use assessments on a small scale. However, the assessments’ usefulness at national level was inhibited by limited monitoring capacity and knowledge on post-deforestation land use. The government was eager to obtain this national-level information, thus contributing to improved monitoring and reporting of land-use change and REDD+.

The Ethiopian government places a strong emphasis on restoring degraded lands and increasing forest cover. While this work is largely carried out by local communities, there is little information on the role that communities play in collecting and sharing data about their restoration activities and about how information collected through participatory monitoring can contribute to monitoring restoration efforts at the national level.

Ethiopia is an active REDD+ country and is expecting results-based payments through several channels. To be eligible, Ethiopia needs to establish a Safeguards Information System (SIS, Warsaw decision 12/CP.19). This requires establishing an effective system for forest monitoring and safeguards at different governance levels. In 2018, Ethiopia established a REDD+ guidance document that outlines the goals, objectives and scope of the SIS, and safeguards indicators adopted to the Ethiopian context. Goals include designing a sustainable, effective, participatory and transparent SIS.

Peru

In 2020, the Peruvian NDC updated its ambition with national emissions reduction targets increasing from 20% to 30% as an unconditional goal and from 30% to 40%, as a conditional goal. The targets also include the Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) and Agriculture sectors.

The updated NDC presents a strong adaptation component, but lacks details on sectoral targets, linkages with SDGs and measurable forest targets. Although Peru has stated its intention to reach net zero emissions by 2050—and has stated its intention to update its Climate Change National Strategy— it is unclear what role the land-use sector will play.

In addition, there is a need to address emissions from agricultural land; over 30% of the country is currently dedicated to agriculture and this percentage is growing. In 2019, the LULUCF sector was reported to contribute 51% to GHG emissions in Peru (about 97 kt CO2e), mainly related to forest land conversion for agricultural use and other activities that cause degradation in the Peruvian Amazon. Thus, forest management and conservation are central to the mitigation of climate change strategy of the country.

As deforestation is one of the primary sources of GHG emissions in the country, more accurate estimates of GHGs from land use will support the implementation of climate change measures into national policies, strategies, and planning.

In recent years, the area of palm oil plantations in Peru established in degraded secondary forests has been increasing. In part, this has been promoted by industry stakeholders and the government to prevent encroachment of palm oil into primary forest. However, the impact of this conversion on GHG emissions has only been estimated using default emission factors, and Peru was lacking country-specific emission factors.

Peru implemented a unique program of incentive payments to Indigenous communities for forest protection in the Amazon rainforest. Payments are conditional on communities maintaining the forest in their territory and carrying out specific activities, such as forest patrolling. Throughout the program’s implementation, some communities have chosen not to participate, while others have dropped out before completing the five-year period or have been suspended, for example because of difficulties fulfilling reporting requirements. The reasons for this dynamic were poorly understood and presented a challenge for supporting the long-term sustainability of community monitoring.

Peru implemented an alert-driven community-based monitoring program. Satellite-based alerts of deforestation events are communicated to communities, which then carry out a verification on the ground. The system was paper based, which led to delays in data collection and often ambiguity in the collected data regarding the causes of the deforestation events.

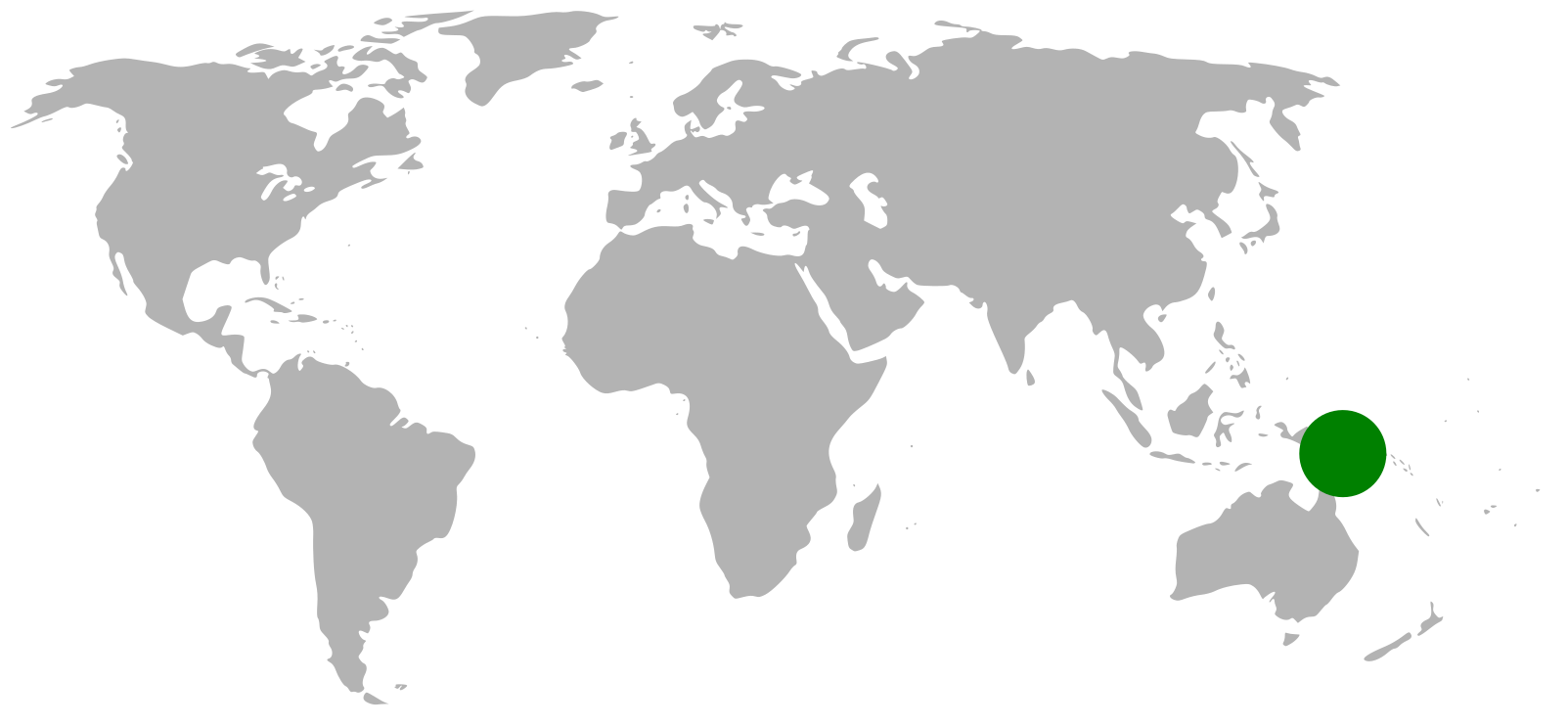

Papua New Guinea

The Papua New Guinea representative at UNFCCC has been a pioneer in advancing climate change policies, particularly through its efforts to address deforestation and forest degradation. Alongside Costa Rica, PNG introduced in the UNFCCC negotiations the concept of reducing emissions from deforestation as a dual approach to combat global warming while fostering economic opportunities for developing nations. This innovative idea laid the foundation for the global mechanism known as RED (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation), which evolved over a decade of negotiation and refinement within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The mechanism expanded into REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) and later into REDD+.

Papua New Guinea was also among the first countries to engage in international multilateral initiatives like the UN-REDD Programme and the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) of the World Bank, signaling its commitment to global climate action. These programs provided PNG with access to technical expertise, capacity-building opportunities, and financial resources to develop foundational systems such as its National REDD+ Strategy and Forest Reference Level.

However, the outcomes were not without challenges. Issues such as delays in implementation, limited stakeholder engagement, and governance weaknesses hindered the full realization of these programs’ potential. One of the main constraints was also the limited capacity of the UN and World Bank to navigate Papua New Guinea’s unique socio-political complexities, including its fragmented governance structures and customary land tenure system, leading to slow implementation and challenges in ensuring equitable and inclusive outcomes.

Today PNG is still receiving support from international actors, and the climate change land related actions have been expanded also to fishery and agriculture sectors.

In PNG, Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) own 97% of the land and play a critical role in biodiversity conservation through their customary land management practices. However, their engagement in any formal nature conservation, climate mitigation and adaptation efforts remains limited due to poor consultation, unresolved land rights issues, insufficient capacity, and weak legal protections.